It starts as a shortcut.

A team connects an AI agent to a workflow to clear a backlog. Someone grants it access to an internal system so it can operate without constant supervision. The permissions are narrow at first—just enough to work—and the agent performs exactly as expected, handling tasks without any obvious side effects.

So it stays. Over time, the scope expands. The agent gets access to another system, then another. It starts triggering actions automatically, running quietly in the background, using authority accumulated incrementally, without a single owner or point of review.

Eventually, the agent stops feeling like an experiment and starts behaving like infrastructure. It’s now acting inside production systems with real permissions and real consequences.

And most organizations don’t even know it's there.

This is how shadow agents take hold

What turns these AI agents into a risk isn’t how they start. It’s how easily they disappear into normal operations.

They’re often not introduced through formal deployment processes or tracked like traditional applications. Most arrive through scripts, integrations, or embedded features, picking up access gradually as teams adapt them to new tasks. No single change feels significant enough to flag. Each permission makes sense in context.

That incremental growth is what makes the agents hard to see.

Responsibility is fragmented. The team that created the AI agent may not own the systems it now touches. The teams that rely on it may not know how it was authorized. Over time, the agent becomes part of the workflow—without ever becoming part of the inventory.

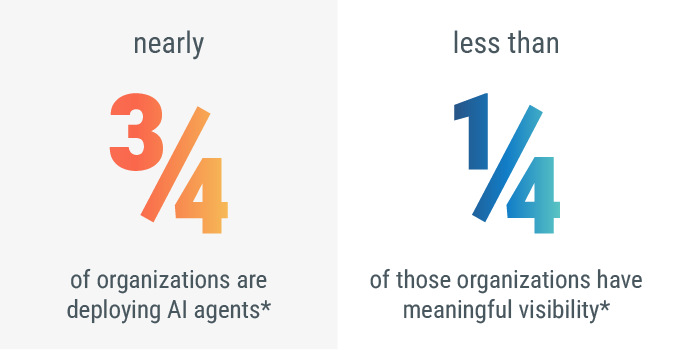

Shadow agents don’t spread because organizations ignore risk. They spread because speed, autonomy, and decentralization are already built into how modern teams work—and the same shortcut gets taken hundreds or even thousands of times across a single organization.

*Source: The State of Agentic AI Security 2025

How shadow agents break existing security assumptions

Most enterprise security models assume two things: that systems are known, and that authority is deliberate.

Shadow agents violate both.

They don’t show up as users. They don’t behave like traditional applications. They don’t follow the lifecycle patterns security teams have spent years building controls around. Instead, they exist somewhere in between—part script, part service, part automation—accumulating access without ever being treated as a first-class identity.

That’s where the assumptions start to fail.

Security teams are used to answering questions like: Who owns this system? What credentials does it use? What’s it allowed to do? Shadow agents make those questions harder to answer because ownership is diffuse, permissions are inherited over time, and behavior evolves quietly as the agent is adapted to new tasks.

The result is a growing class of autonomous actors operating with real authority, but without clear identity, consistent policy, expanding intent, or reliable oversight.

This isn’t a tooling gap. It’s a model gap.

Most security frameworks were built for humans and machines that behave predictably. Shadow agents don’t fit either category. They act independently, interact across systems, and persist because they’re useful—not because they were formally approved.

Until organizations rethink how identity, governance, and control apply to autonomous systems, shadow agents will continue to operate in the space between what’s allowed and what’s visible.

Why identity breaks

Most security programs are built on a simple premise: If you can identify something, you can control it.

That assumption has been under pressure for years as non-human identities multiplied across cloud services, APIs, and automation. AI agents push it past a tipping point—not because they add more identities, but because they introduce autonomy.

AI agents challenge identity models in a few specific ways:

- They don’t arrive as first-class identities: Agents are often assembled from scripts, integrations, and third-party tools, borrowing credentials instead of being issued their own.

- Their authority accumulates over time: Permissions are added incrementally as agents are adapted to new tasks, often without a single owner reviewing the full scope of access.

- Their behavior evolves: Agents don’t just authenticate and execute fixed tasks. They make decisions, initiate actions, and interact across systems in ways that change as workflows change.

- They blur accountability: When agents act using shared roles or inherited credentials, it becomes difficult to separate agent behavior from system behavior—or to trace actions back to a clear owner.

AI agent trust has become non-negotiable

As AI agents become more capable and more common, the gap between autonomy and oversight will widen—not because organizations are careless, but because existing security models weren’t built for delegated decision-making at this scale.

The near-term shift is straightforward: Agents will stop being treated as tools and start being treated as actors. That means every AI agent will need a verifiable identity, explicit ownership, and clearly bounded authority—just like any other entity trusted to operate inside production systems.

Organizations that get ahead of this will make one critical change. They’ll stop asking whether an agent is useful and start asking whether it’s authorized.

That shift brings practical implications. AI agents will need to be discoverable by default, not found after the fact. Permissions will need to be assigned deliberately, not inherited accidentally. And revocation—whether through credential rotation, policy enforcement, or a kill switch—will need to be fast enough to matter when something goes wrong.

The alternative is less abstract.

If shadow agents continue to accumulate without identity, governance, or enforcement, incidents won’t look like traditional breaches. They’ll look like unexplained actions: data moved without a clear source, systems changed without an obvious initiator, decisions made without a human in the loop—and no clean way to trace or stop them.

That’s the trajectory organizations are on unless agent trust becomes a first-class security concern.

What securing agentic AI actually requires

Securing agentic AI doesn’t require reinventing security from scratch—but it does require extending long-standing trust models to entities that were never designed to fit inside them. In practice, that means treating AI agents as first-class participants in the enterprise trust fabric.

At a minimum, organizations need to be able to do four things:

- Give every agent a verifiable identity: Agents can’t remain anonymous abstractions stitched together from borrowed credentials. Each one needs a distinct, cryptographically verifiable identity that makes its actions attributable, auditable, and enforceable across systems.

- Establish clear ownership and delegated authority: Every agent should have an accountable owner and explicitly defined permissions. Authority should be scoped to what the agent is meant to do—not what’s convenient to grant—and revisited as the agent evolves.

- Make agents discoverable by default: If an organization can’t inventory its agents, it can’t govern them. Discovery can’t depend on manual documentation or tribal knowledge; it has to be embedded into how agents are created and deployed.

- Enforce policy and revoke access decisively: When an agent behaves unexpectedly or becomes compromised, organizations need the ability to intervene immediately. That means revocation, rotation, or shutdown mechanisms that work at machine speed—not after an incident review.

This is where intelligent trust becomes essential.

As autonomy increases, trust can no longer be static or implied. It has to be continuously established through identity, cryptography, policy, and real-time enforcement. Intelligent trust is an evolution of digital trust that allows organizations to verify not just who an agent is, but what it’s allowed to do at any given moment—and to adapt that trust as conditions change.

Building trust into agentic systems with DigiCert

Managing certificates, keys, and identities at machine scale is challenge enough. Adding autonomous agents only raises the stakes. But the goal isn’t to eliminate shadow agents entirely—it’s to shine light on them, making agentic systems visible, governable, and controllable so autonomy can’t scale beyond reach.

DigiCert ONE and Trust Lifecycle Manager help companies establish and manage cryptographic identity across users, machines, devices—and now, AI agents—so trust is continuous, auditable, and resilient over time.

For organizations beginning this journey, the next step isn’t perfection. It’s visibility. From there, identity, governance, and enforcement can follow—before shadow agents become impossible to unwind.